Morning:

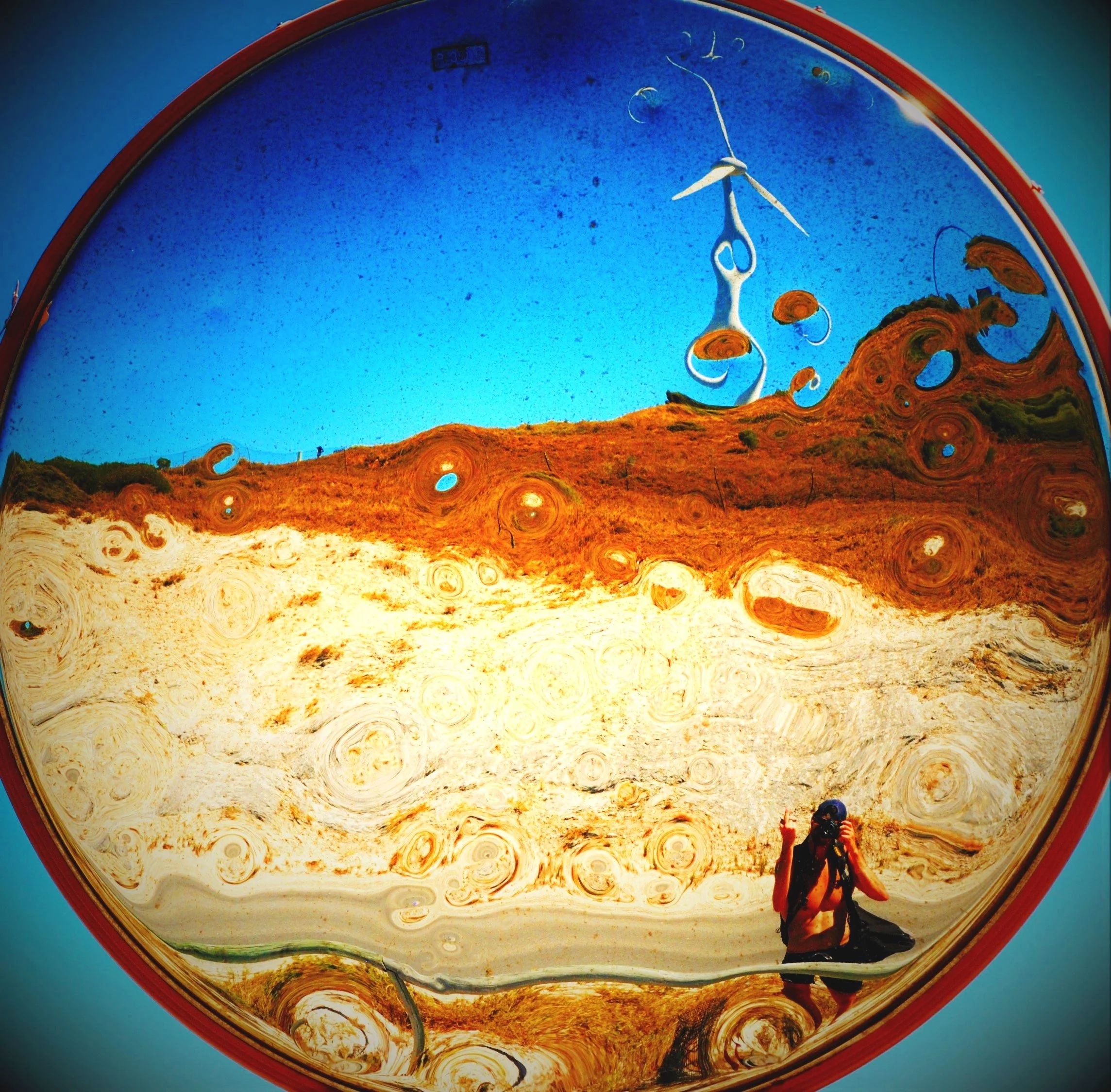

This coastline is wind-blown, though not by force, but by a persistent breeze conjured in the west that quietly buffets the sand and the water though an infinity of tiny particular collisions. Over millennia, it has sculpted this small stretch of coastline against the rising sun. It counts on the intermittent help of more belligerent forces such as storms and the ocean itself. But tides rise and fall, storms roll in and out, and still, there is always the breeze.

The lagoon bobs under this western fetch, its waves strolling along unhurried like the swaying of the palms, like this entire morning around them. A tern rolls and dives for fish, providing the only rupture in the otherwise unbroken surface of this small lagoon. Over the southern bank, the ocean dissents against the solitude of the deeper waters, the same waters in which the locals are preparing to sink their nets. In a pale morning, the fishermen gaze from this embankment out beyond the curvature of earth-- their slice along the Gulf of Guinea, the warm currents which entice the ships at the beginning of each day, and return them (if their luck is good) before a hot sun claims its own sky.

It takes almost an entire community to set the boats to course and haul in the nets. The surf is rough on steep sand and the skiffs heavy and water-logged. Waves boil and erupt almost immediately as one enters, conditions that mean beating the breakers requires the sinew and strength of more than a few men. It requires even more to bring those same boats ashore later in the morning. The nets, however, are another matter entirely.

Being brought to shore from over a kilometer out, these drag nets are a task for every village member. While some men and women heave, pitting their bodies against the unforgiving lines, others sit beside curling up reclaimed net and shoring-up the buoys. Some young boys, whose feet barely touch the ground, take spots along the line next to the men, grunting and chanting with all amount of earnestness and enthusiasm but providing little resistance against the tide. Behind them, young girls neatly coil the lengths of rope into piles almost as tall and slender as they. Over the din of the waves, an old man chants rhythmically, conducting the strain and pulse of both the rope and its handlers in the same stroke.

It took me a while, and though my Ewe is still elementary, the instructions within the song are quite self-explanatory. To heave in unison, the song is slow and steady, a drumbeat almost, “dun…..dun…..dun…..”. When opposing lines need to converge, as they do at intervals throughout the process, the slow drum becomes a drum-roll of “right, right, right, right…”--every man jumps over the to the inside of the lines and pulls together at their sides. Once the end of the nets enters the breakers, the instructions take their cue from the waves themselves, it’s “pull…pull…pull...” when the waves break, and “hold…hold…hold…” as the wicked undercurrents relent against relinquishing the quarry. Feet are dug and legs sunk up to the knees into the sand as hands and backs are drawn taught. As I do my tiny part in this great orchestra, as I struggle to keep my fingers wrapped around this quivering rope, I am sure that either the lines or the bodies will snap under the strain. Neither occurs and, after over an hour and a half of an exhausting fight, we are rewarded with a bounty of shrimp and sunfish and crabs and a host of exotic fish that I have never seen.

These are fishing communities--there are few lone fishermen here. You just wouldn’t catch much, or maybe you would simply never make it home going at these waters alone.

Afternoon:

I ask the bartender expectantly, already knowing his answer but wanting to hear it anyway, “Do you know if I could score some bud around here.” So far in my travels, and especially in Africa, this question almost always produces an affirmative response and by extension, a very fine evening.

He smiles discretely, “You want it tonight?”

“Eh,” I reply, “would be nice, but no worries, whenever you can.”

“How about this in the meantime…” He reaches under the bar and produces a clear bottle shaped like a skull. Inside is an alcoholic tea steeped by beautiful green sprigs of marijuana. Palm wine tincture--home-brewed with locally grown herb, its normal transparency having stained into the finest hues of seaweed and sea-foam green. He shakes it up and its contents dance and colors swirl like a tropical snow-globe from Rasta heaven. I hear the sound of the ocean rising in my ears and someone is playing a drum….things just got interesting.

It starts in your core, with the indistinct lines between the fire of the herb and the warmth of the alcohol, and washes with your blood down your limbs and into your lesser extremities. And all of a sudden, you are floating over the earth. And this is where you stay for a while and that is just fine with me.

Staring at the ocean while flying--an experience which I cannot recommend enough--induces a completely different state of being. Moments are uncounted waves and hours are the occasional passing bird. I must be quite a sight: pale legs stretched out in the sun, red-star cap pulled down over my eyes, sunglasses long forgotten at my side and salsa music playing on my radio. Between my lips rests a smoke, recently extinguished by the always-breeze, but I find no rush to relight my herbal friend. We’ll get there eventually. Oh, we will get there indeed.

Night:

After a day of deep thought, a letter written to a friend at night:

I have had exactly 1 shower in the past 10 days--the rest of the time I have been bathing in the ocean and drying by the sun. What a strange animal I am, indeed, certainly not fit for civilized society. Last night I feel asleep, bottle of wine in hand, under an open thatch shack on the banks of a lagoon with the sea rumbling just over to the south. I don't know why, but I have always found the ocean healing, and as much to the body as the soul. It's always been my escape and my refuge and I have come to attribute to it almost supernatural medicinal powers: infected bug-bite--the salt water will heal it; bad head cold--the mist off the water will clear it right up; sad and alone--there are an endless series of tempestuous waves for company. And if that fails, if you find the waves to be unruly company, nothing exudes loneliness with quite the same grace as a sea bird. You can always take solace in watching an albatross or a petrel, birds that know a solitude you can never imagine.

I have been gluttonous with the sea these past few days but I do not intend to stop. There is nothing, nothing in this world I love more than sitting quietly on the shore and listening to music while the waves dance. This song in particular I felt I would pass along:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=YhCpNmMFfbM

You probably know it, but my lord, if this shit doesn't make me wanna fly. To quote the words of Joseph Campbell (some of the sweetest words ever uttered), "[Life can be] a mild, slow-burning rapture". That's what this song says to me.

"I hope I don't become a good boy, slow and strong,

minding my manners and playing along.

A pet for my dear Doe, Jane.

I used to nip at the heels and bay at moon

now I sit and stay like the good dogs do."

A reminder to myself, but perhaps redundant at the moment, to always remain wild and unkempt and a bit rough around the edges. Like the ocean, I hope to stay deep and genuine at the core but unruly as the waves on the surface. May a suit always sit awkwardly on my shoulders, may I always make a mockery and a spectacle of diner parties, and may dirt ever welcome me and the ocean remain my fountain of youth.

Yeah, that's alright with me.

from the beach, somewhere,

-mario