There is a child sitting next to me, his head resting in his mothers lap. He is exhausted and his small body hangs like a collapsed tent on the bones of his tiny frame. His soccer jersey is a mine-field pocked with holes of vary size and geometry; the remaining fabric is occupied by stains of ash and dirt haphazardly scribbled in-between stripes of red and white, the colors of Paraguay's 'Selecion Nacional'.

Streaks of soot cross his face with the tragic effect of hollowing his already slender cheeks--each dash of powdered carbon, like some temporary scar, mumbling its own sad story. His eyes are unassuming and within them resides the calmness of defeat, the quietness of his obvious hunger. They echo with the shock of having unexpectedly glanced too far beyond the carefree frontiers of childhood bliss and into a reality that is as unnerving as it is inevitable. He hardly moves, says nothing. With one finger, he traces the veins across the back of his mother's hand.

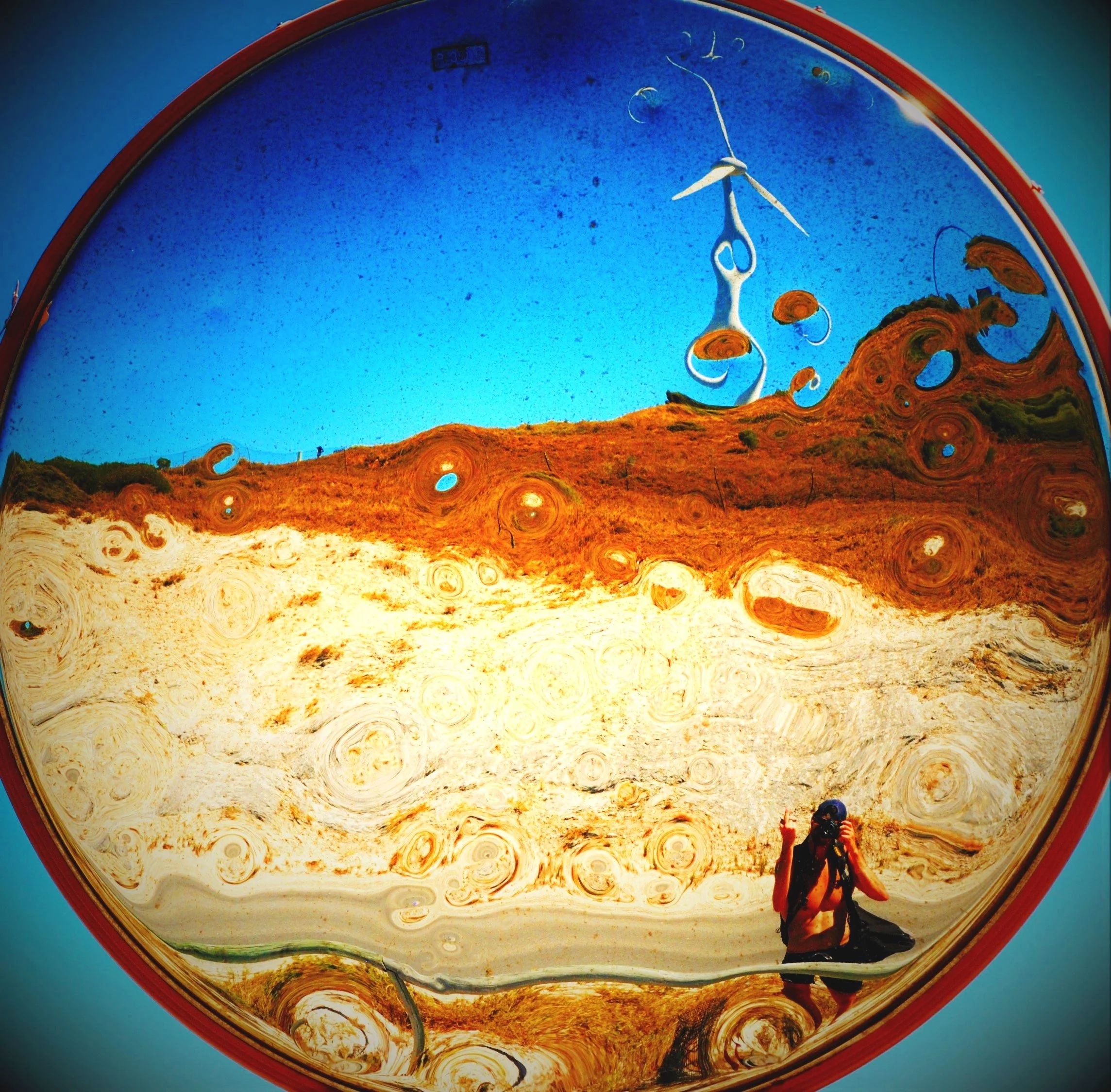

His mother's head remains balanced in the cradle of her opposing palm. She is looking away from the crowd of people gathered at her feet, away from the rest of her weary children, away from the man yelling defiantly some meters away. She is looking instead towards some nothing, somewhere over the horizon. There is a billowing plume of smoke and the haze of heat that rises over that distant, barren pasture. Those around her seem to be intentionally avoiding her same orientation. I, however, am not so disciplined--torn between all of these quietly persistence gazes, the small battles of will dancing across the wrinkles and lines in the faces all around me, and that point over the hill where something is still burning. There has been an attack today on something very profound and very dear to these people, that much is clear. There is a war going on here, but it is a silent war.

Let me start where things usually begin, somewhere in history. I won’t tell the whole history, for that would take too long, it would be too massive an undertaking, and these humble people seem to deserve something much more than an esoteric essay on historical causes and effects. This is not a justification anyways (as history is often construed to be); this is a real story with real people and real events. Lets not dilute that with any nonsense. What I am about to tell you has happened and is happening right now in my little corner of the world.

Several months ago, a group of landless peasants who live near my home in the Cordillera district of Paraguay, South America made the collective decision to illegally occupy a small fraction of the massive swath of private property that borders one edge of my community. Almost thirty families moved from the shanty-town encampment--where they had been living in small tents for almost a year without running water or electricity--into this fertile area of fallow land. They began by clearing trees, planting crops, building more permanent structures for homes and creating actual lives for themselves, as opposed to the semi-mobile, barely-scraping-food-together type of existence they had previously been leading.

Politics here in Paraguay, especially in regards to the landless peasant groups (Campesinos Sin Tierra--see my other blog South American Politics for more info), have been quite volatile over the past few months. Already this year, the clashing interests of large land owners and disenfranchised Paraguayans have spilt blood, impeached a President and solicited international economic sanctions. For many decades, this important and controversial issue has bubbled just below the tumultuous surface of the Paraguayan political current. As of this week, these tensions reached yet another flash point as an army of national police was used to forcefully remove these poor peasants of my community from the small patches of earth that they had only recently come to call their home.

Not only did this fully armed, battle-ready police force of over a hundred officers arrive in the early morning hours to evict these people (families of men, women, children and babies), but they proceeded to slash their crops and burn their small houses to the ground as a means to discourage their return to the area. The peasants, who had finally staked claim and started a simple, poor, yet dignified life for themselves, were, in a matter of minutes, dispossessed of absolutely everything in the world but the clothes on their back and the half-sleeping children walking at their side. The message was clear: private property, market interests and deep-pockets trump human rights, even basic human dignity, every time. My neighbors were cast as the roll of 'collateral damage' in the great theater that is our global, capitalist drama. It is a minor character, one without any speaking parts, but poignant nonetheless and utterly essential for the show to go on.

Politics, economics, laws aside, imagine this if you will: you are a hard working farmer who wakes up every morning before the sun to toil and sweat in the fields while your wife remains at home cooking and caring for your small children and your newly born baby. Work is hard, life is harder, you have few things, no health care, you lack water or electricity, you cook over an open fire, your diet is lacking in nutritional value, you are subsisting at a very fundamental level. But at least, you have a field to call your own, a home that is the product of your own work in the forests, felling trees and stitching thatch together for the roof, and a family to sit around the fire with at night.

One morning you wake up to army helicopters and machine-gun wielding police at your door. They gather you along with your wife and children and force you from your home. In your wake, you see them cut the crops you have sown and raised for months in the hot South American sun, you watch them set fire to that small house, your home, and burn it to the ground. You are then told that you can never return to this place for fear of arrest or more brutal police treatment. You have no bed to sleep in, no roof over your head, no food to fill your belly or the bellies of your malnourished, fly-bitten children. Legally, literally, realistically, you can do nothing but wait and stare at that horizon where your home used to be.

There is no acceptable ethical or rational justification for the treatment of human beings this way. It is undignified, dehumanizing, unjust. But this is the reality of our world--it is a very immediate reality of my world, as these families, these hungry children are my neighbors and friends--but this is still a very real part of our world. History will tell you why, modern politics will show you how, but the way in which such events have come to pass is not the exception, it is the heartbreaking norm and one that has been largely sheltered from our eyes as citizens of the All-Mighty American Empire. Yet, it is the very things that we do, the decisions we make on a daily basis, the foundational philosophies that govern the lives of those in the first-world that have contributed to the rise of this system of economically-stratified, monetarily-prioritized human beings.

The Campesino Sin Tierra movement is just one of countless other organized activist groups across the globe reacting to the ubiquitous phenomenon of disenfranchisement by means of economic imperialism. The Zapatistas of the Chapas region in Mexico, tribal-rights groups from the Niger Delta, Brazil's MST (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra), are just a few among the multitude. These organizations represent peoples that have played (in their own small way) by the rules of the globalized marketplace and yet, lost out completely every time. Now many struggle to feed themselves and their families.

For us in the first-world, it's hard to contextualize or understand the ideas that drive people to knowingly break the law in search of even marginally better lives. The factors that motivate people to rise up so passionately remains a mystery to most because our perspective on such issues only includes half of the whole picture. Where others see their livelihoods compromised and their lives disrupted we simply see an economic system that allows us to sustain our gluttonous lifestyles, a system that grants certain countries (primarily the United States) disproportionate quantities of the global bounty.

Most of us have never spent days on end with an empty stomach nor have we toiled for months in the hot sun to coax a small parcel of dirt into production. Most of us have never had to live in a shack without running water. In fact, most of us have never even witnessed, let along experienced first-hand, the cards dealt to those living in abject poverty, except for maybe occasionally and only from the safe distance made possible via TV infomercials. We have been too blinded by the unquestioned virtues of the free-market and globalization because those are the only sides of the equation to which we are ever exposed.

But what is happening here to these families, this is neither freedom nor democracy nor liberty nor any of those wonderfully bastardized catch-phrases wielded in the name of modern capitalism and global neo-liberalism. This is the underbelly of the beast, the opposite end of the capitalist spectrum, the part that is all too often written-off as unavoidable fallout resulting from a system that is otherwise considered pure and infallible. The individual lives of each of these human beings constitute, piece by piece, the briefly acknowledged "human toll" that sits as a footnote on a page in the annals of political and economic policy.

But to me, these people cannot just be categorized and simplified so easily; to me, these people have names, faces, each one of them has a different personality, different ways of speaking to me, variable senses of humor, even subtly different way to pour and share tereré. Unfortunately, the ideal of the 'capitalist individual' is not contingent upon such nuances of a human being or their spirit, but instead, only upon one's ability to command finances and capital to achieve certain aims.

What is happening here is just one part of an important chapter in the story that is the tragedy of our times. While Fukayama may have declared "the end of history" all those years ago, history has instead soldiered on. Surely, the communist tide has waned, but the capitalist ideology is still challenged every day by those very people it has bulldozed, ignored and forgotten. People yearn for a rhetoric of inclusion, a system that unites hopes and concerns from all tiers of life, a collective philosophy behind which we can all rally as we face the unprecedented challenges of our shared future. Instead, there continues to exist an inconceivably profound schism between the richest and the poorest among us, the winners and the losers of our world. We have allowed ourselves to construct artificial pedestals to compartmentalize our species and neatly delineate our world, enabling us to avoid the uncomfortable confrontation with the abject conditions of so many others. There is no greater lie on earth.

The actions that have been carried out here in my community, the events that have ravaged the already difficult lives of my neighbors and friends, have taken place at the hands of a few. But it is through the passivity and complicity of the many through which they achieved legitimacy and have been allowed to perpetuate. It is my sincere hope that we never reach "the end of history", that people will unite for common goals instead of against common enemies, that each of us can personally participate in the construction of a better future. There is too much at stake to do otherwise.

from this world, from our world

-little hupo

Streaks of soot cross his face with the tragic effect of hollowing his already slender cheeks--each dash of powdered carbon, like some temporary scar, mumbling its own sad story. His eyes are unassuming and within them resides the calmness of defeat, the quietness of his obvious hunger. They echo with the shock of having unexpectedly glanced too far beyond the carefree frontiers of childhood bliss and into a reality that is as unnerving as it is inevitable. He hardly moves, says nothing. With one finger, he traces the veins across the back of his mother's hand.

His mother's head remains balanced in the cradle of her opposing palm. She is looking away from the crowd of people gathered at her feet, away from the rest of her weary children, away from the man yelling defiantly some meters away. She is looking instead towards some nothing, somewhere over the horizon. There is a billowing plume of smoke and the haze of heat that rises over that distant, barren pasture. Those around her seem to be intentionally avoiding her same orientation. I, however, am not so disciplined--torn between all of these quietly persistence gazes, the small battles of will dancing across the wrinkles and lines in the faces all around me, and that point over the hill where something is still burning. There has been an attack today on something very profound and very dear to these people, that much is clear. There is a war going on here, but it is a silent war.

Let me start where things usually begin, somewhere in history. I won’t tell the whole history, for that would take too long, it would be too massive an undertaking, and these humble people seem to deserve something much more than an esoteric essay on historical causes and effects. This is not a justification anyways (as history is often construed to be); this is a real story with real people and real events. Lets not dilute that with any nonsense. What I am about to tell you has happened and is happening right now in my little corner of the world.

Several months ago, a group of landless peasants who live near my home in the Cordillera district of Paraguay, South America made the collective decision to illegally occupy a small fraction of the massive swath of private property that borders one edge of my community. Almost thirty families moved from the shanty-town encampment--where they had been living in small tents for almost a year without running water or electricity--into this fertile area of fallow land. They began by clearing trees, planting crops, building more permanent structures for homes and creating actual lives for themselves, as opposed to the semi-mobile, barely-scraping-food-together type of existence they had previously been leading.

Politics here in Paraguay, especially in regards to the landless peasant groups (Campesinos Sin Tierra--see my other blog South American Politics for more info), have been quite volatile over the past few months. Already this year, the clashing interests of large land owners and disenfranchised Paraguayans have spilt blood, impeached a President and solicited international economic sanctions. For many decades, this important and controversial issue has bubbled just below the tumultuous surface of the Paraguayan political current. As of this week, these tensions reached yet another flash point as an army of national police was used to forcefully remove these poor peasants of my community from the small patches of earth that they had only recently come to call their home.

Not only did this fully armed, battle-ready police force of over a hundred officers arrive in the early morning hours to evict these people (families of men, women, children and babies), but they proceeded to slash their crops and burn their small houses to the ground as a means to discourage their return to the area. The peasants, who had finally staked claim and started a simple, poor, yet dignified life for themselves, were, in a matter of minutes, dispossessed of absolutely everything in the world but the clothes on their back and the half-sleeping children walking at their side. The message was clear: private property, market interests and deep-pockets trump human rights, even basic human dignity, every time. My neighbors were cast as the roll of 'collateral damage' in the great theater that is our global, capitalist drama. It is a minor character, one without any speaking parts, but poignant nonetheless and utterly essential for the show to go on.

Politics, economics, laws aside, imagine this if you will: you are a hard working farmer who wakes up every morning before the sun to toil and sweat in the fields while your wife remains at home cooking and caring for your small children and your newly born baby. Work is hard, life is harder, you have few things, no health care, you lack water or electricity, you cook over an open fire, your diet is lacking in nutritional value, you are subsisting at a very fundamental level. But at least, you have a field to call your own, a home that is the product of your own work in the forests, felling trees and stitching thatch together for the roof, and a family to sit around the fire with at night.

One morning you wake up to army helicopters and machine-gun wielding police at your door. They gather you along with your wife and children and force you from your home. In your wake, you see them cut the crops you have sown and raised for months in the hot South American sun, you watch them set fire to that small house, your home, and burn it to the ground. You are then told that you can never return to this place for fear of arrest or more brutal police treatment. You have no bed to sleep in, no roof over your head, no food to fill your belly or the bellies of your malnourished, fly-bitten children. Legally, literally, realistically, you can do nothing but wait and stare at that horizon where your home used to be.

There is no acceptable ethical or rational justification for the treatment of human beings this way. It is undignified, dehumanizing, unjust. But this is the reality of our world--it is a very immediate reality of my world, as these families, these hungry children are my neighbors and friends--but this is still a very real part of our world. History will tell you why, modern politics will show you how, but the way in which such events have come to pass is not the exception, it is the heartbreaking norm and one that has been largely sheltered from our eyes as citizens of the All-Mighty American Empire. Yet, it is the very things that we do, the decisions we make on a daily basis, the foundational philosophies that govern the lives of those in the first-world that have contributed to the rise of this system of economically-stratified, monetarily-prioritized human beings.

The Campesino Sin Tierra movement is just one of countless other organized activist groups across the globe reacting to the ubiquitous phenomenon of disenfranchisement by means of economic imperialism. The Zapatistas of the Chapas region in Mexico, tribal-rights groups from the Niger Delta, Brazil's MST (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra), are just a few among the multitude. These organizations represent peoples that have played (in their own small way) by the rules of the globalized marketplace and yet, lost out completely every time. Now many struggle to feed themselves and their families.

For us in the first-world, it's hard to contextualize or understand the ideas that drive people to knowingly break the law in search of even marginally better lives. The factors that motivate people to rise up so passionately remains a mystery to most because our perspective on such issues only includes half of the whole picture. Where others see their livelihoods compromised and their lives disrupted we simply see an economic system that allows us to sustain our gluttonous lifestyles, a system that grants certain countries (primarily the United States) disproportionate quantities of the global bounty.

Most of us have never spent days on end with an empty stomach nor have we toiled for months in the hot sun to coax a small parcel of dirt into production. Most of us have never had to live in a shack without running water. In fact, most of us have never even witnessed, let along experienced first-hand, the cards dealt to those living in abject poverty, except for maybe occasionally and only from the safe distance made possible via TV infomercials. We have been too blinded by the unquestioned virtues of the free-market and globalization because those are the only sides of the equation to which we are ever exposed.

But what is happening here to these families, this is neither freedom nor democracy nor liberty nor any of those wonderfully bastardized catch-phrases wielded in the name of modern capitalism and global neo-liberalism. This is the underbelly of the beast, the opposite end of the capitalist spectrum, the part that is all too often written-off as unavoidable fallout resulting from a system that is otherwise considered pure and infallible. The individual lives of each of these human beings constitute, piece by piece, the briefly acknowledged "human toll" that sits as a footnote on a page in the annals of political and economic policy.

But to me, these people cannot just be categorized and simplified so easily; to me, these people have names, faces, each one of them has a different personality, different ways of speaking to me, variable senses of humor, even subtly different way to pour and share tereré. Unfortunately, the ideal of the 'capitalist individual' is not contingent upon such nuances of a human being or their spirit, but instead, only upon one's ability to command finances and capital to achieve certain aims.

What is happening here is just one part of an important chapter in the story that is the tragedy of our times. While Fukayama may have declared "the end of history" all those years ago, history has instead soldiered on. Surely, the communist tide has waned, but the capitalist ideology is still challenged every day by those very people it has bulldozed, ignored and forgotten. People yearn for a rhetoric of inclusion, a system that unites hopes and concerns from all tiers of life, a collective philosophy behind which we can all rally as we face the unprecedented challenges of our shared future. Instead, there continues to exist an inconceivably profound schism between the richest and the poorest among us, the winners and the losers of our world. We have allowed ourselves to construct artificial pedestals to compartmentalize our species and neatly delineate our world, enabling us to avoid the uncomfortable confrontation with the abject conditions of so many others. There is no greater lie on earth.

The actions that have been carried out here in my community, the events that have ravaged the already difficult lives of my neighbors and friends, have taken place at the hands of a few. But it is through the passivity and complicity of the many through which they achieved legitimacy and have been allowed to perpetuate. It is my sincere hope that we never reach "the end of history", that people will unite for common goals instead of against common enemies, that each of us can personally participate in the construction of a better future. There is too much at stake to do otherwise.

from this world, from our world

-little hupo