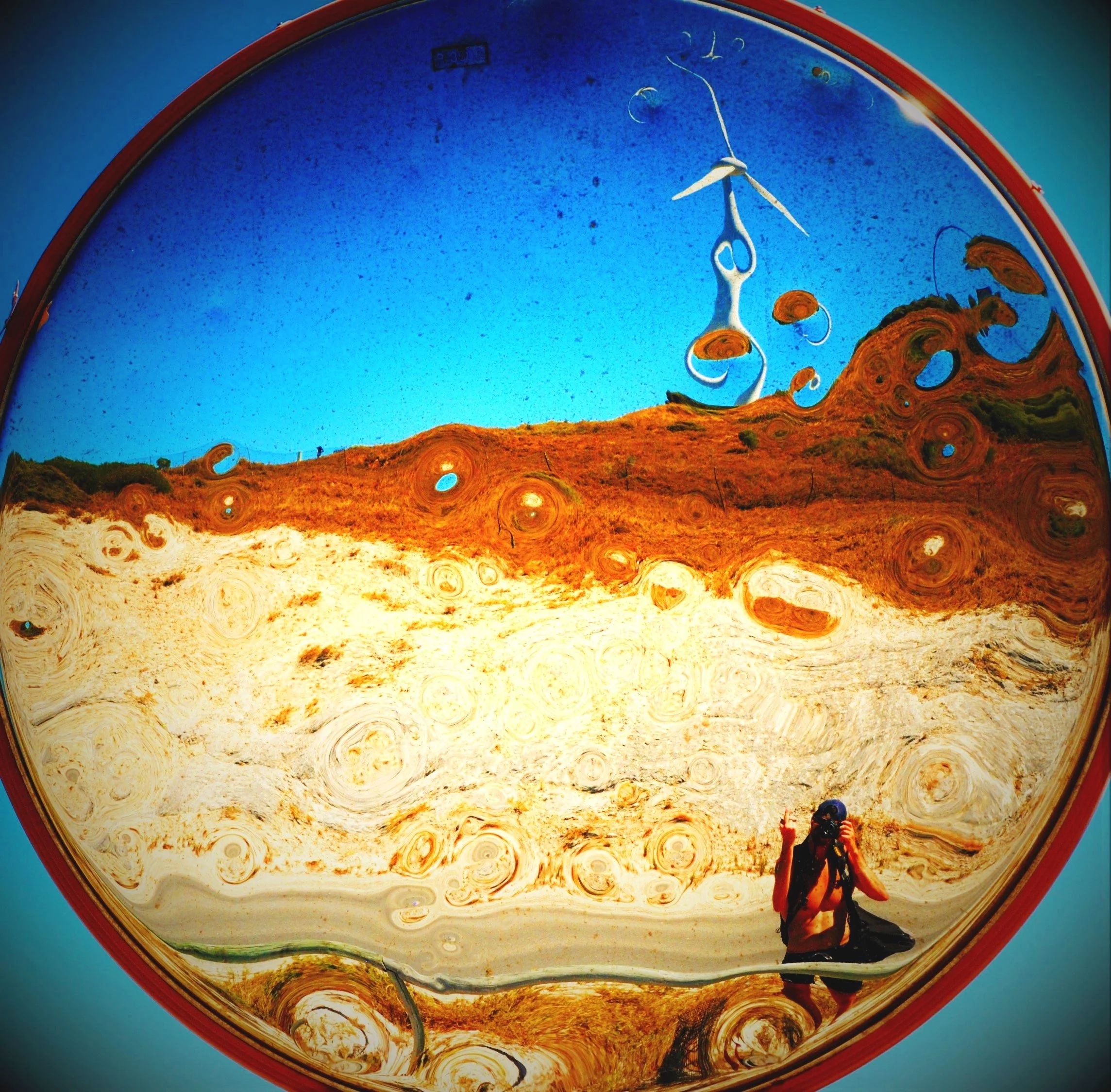

Winter on the Wild Coast is white-crowned, wind-tossed waves

breaking along an empty shoreline. From the bluffs and rolling hills looking

out to sea, migrating whales can be seen playing in the swell with such

regularity that they almost become more of a challenge to miss. Turn inland, and the

rest of the Eastern Cape of South Africa is nothing but big sky country as far

as you can imagine and even then, a bit farther. Communities of concrete houses

and thatch-roof rondevals dot the highlands above the river valleys after which

they are often named. This is Nelson Mandela’s homeland, the place of the Xhosa

people and their herds of stately Ngoni cattle urged along by young boys sometimes

only half-as-tall.

In the mornings, the air is bone-chilling, laden with

moisture as much as cold. This time of year, the sun is in no hurry to herald in the day, bringing the sunrise with it only after a long and lazy struggle

against the horizon. The birds who, with few exceptions, are always

the prudent characters in the forests of the Transkei, set about making

short-work on the full morning air. Ibises and weavers and hornbills skip off

of the treetops like stones across water. The coast is left to the

plovers and gulls and cormorants who run their errands through the surf and

among the rocks, searching out the morning’s taking and leaving the shells and

detritus from their indulgences scattered about for the afternoon sun.

I spent a little under two weeks with a small field team

working in the forests of the Dwessa-Cwebe and Mkhambati Nature Reserves--two

incredible and also incredibly different biodiversity hotspots in the Transkei,

a part of South Africa that stretches from the southern extent of the Eastern

Cape northward, ending on the coast just west of the country of Lesotho. The

forests here teem with a variety of floral and faunal life that can only be

fully appreciated if taken in slowly. We passed our days working various

forests plots that our head scientists, the indomitable Dr. Erica Smithwick, had

set up some years ago with the help of a group of undergraduate students of which I was

one.

Working in the Transkei and soaking in its landscape is incomparable in and of itself. And yet, I found the experience heightened even further by the nostalgia this setting still rings in my mind.

It was 5-years ago now that I found my way to this place during my final

year at university. It was during this initial 3-month trip that I got my first real sense of what kind of work I wanted to do with my life, thanks in no

small part to Dr. Petra Tschakert, the professor and mentor with whom I would

end up working and traveling with for the next few years. It was also during this trip to the Eastern Cape that I actually began this

blog, initiating my own personal journey to learn about the

power of the written word, the potential of my own voice, and my ability to communicate the things I was

experiencing to audiences elsewhere. Then, of course, there were the (inter)-personal dimensions of this first trip to South Africa, but perhaps I

will save that for another time.

Being back on the Wild Coast, walking the same beaches and forests

that I had once come to know, was simultaneously incredible and also disorienting. In the intermittent 5-years, I have traveled literally around the

world to more than a few different countries, living and working for a few

years or months in some, resting for short period of time in others. I

have grown remarkably, both personally and intellectually, through this

wanderlust which still remains unsated. All of this I know and have recognized inherently, but still, seeing

the Transkei and being absorbed once again in that landscape invoked an intense process of introspection that felt almost like trying to

fit a square peg into a round hole. The person I was when I first came here is, in many ways, incompatible with the person that I am now. I

remember the idealism and hubris that accompanied that naive 22-year old

into the South African bush. I remember the freshness and novelty of each

interaction and each experience in my mind. I remember the feeling of confidence born out of books and ideas and few things real. I remember thinking I had any clue

what was going on around me.

And here I am, certainly older and only-possibly a bit

wiser. It is not that I have lost all of those things, just that a half-decade

later, after working in development and academia, with NGO’s and government

agencies in contexts around the globe, I have a much more tempered approach to

the world, to possibility, to who I am and what I can hope to accomplish. The

idealism is not gone entirely, but grand ideologies seem to hold less currency almost daily--nowadays, I tend to treat them more with outright derision as opposed to my once-enthusiastic trumpeting. All of which is not to say that such ideas are no longer important to me, far from it. It is only to say something about what I have come understand better: that ideas in-and-of-themselves are the easy part. The world hardly ever conforms neatly to such things anyway, regardless of one's intention.

Who I am now seems most aptly surmised by Antonio Gramsci's “Pessimism of the intellect. Optimism of the will.” Such an admission would

have disheartened 22-year old Mario, but in reality, it is not a sad or cynical

place to be. In fact, I feel more liberated in my mind at this age, less

tied to the stubborn prescriptions and authority of long-dead thinkers and writers, and more

able to stitch together the philosophies and ideas that I find useful and

applicable to my present work, efforts and experiences. I have gathered and built my own intellectual authority for myself from the things I have done, the places I have gone and the experiences I have had. In the meantime, my utopian vision has been

shot to hell, but in its place, I feel as if I have constructed something infinitely

more valuable: a role for myself to play in the world that actually exists.

As for all those (inter)-personal dimensions, I

am still clueless. This is perhaps the only thing that does not seem to make more sense with

age.

One of my last nights in South Africa before heading out to

Mozambique for a month, I found myself standing on a beach at The Haven,

a small hotel on the Cwebe side of the Mbashe river where I had stayed before. Storm clouds were sitting

low in the sky, shuttering everything but the faintest orange-pink-purple hue of

the setting sun. I stood there facing the ocean and remembered running the

same coastline on a clear morning 5-years ago as a younger man. Being here was,

in so many ways, like meeting my younger self; it was like giving my current

self the litmus test of age to see if I was progressing as should be expected. The

results: inconclusive. I think about the distances I have covered, both

literally and figuratively, and I wonder if I will ever come to a place, a

moment in my life, where I have gone far enough.

As a very special person recently mused to me in those same

forests of Dwessa: in the West, it seems we need to go on physical journeys in

order to also go on personal or spiritual ones. And while I wonder why this is, I also wonder

if it is not the best thing in the world. Then again, I wonder if I would have

a choice either way.

One foot in front of the other--keep pushing that boulder,

dear Sisyphus.

-mario