*Let me preface this blog by first apologizing to my mother, my limbs, and once again, animal rights activists. I would appeal to the fact that food ethics are quite different considerations in this part of the world, but I have used that excuse several times already. Instead, I will own up to the fact that I wanted to have an adventure and the following events unfolded in such a manner as to satisfy that desire almost completely. My rational inhibition is no match for my thirst for adrenaline--a disposition that I keep telling myself I will grow out of, but that only seems to deepen with time...

Several days ago, while drinking tereré with my neighbor, Don Jervacio, I was invited to diner with him and his family the following evening. I agreed happily and asked what we would be having to which he nonchalantly responded in Guarani, “Ja’uta jakaré” (translating directly to mean: we are going to eat crocodile). I was intrigued for several reasons:

I proceeded to ask how far away this river was. They informed me that it was not far, only five kilometers or so. I asked how large was the crocodile they had killed. They informed me that it was a little over 2 meters (that is well over 6 feet, an animal large enough to take down a cow, let alone a person). I asked them how they managed to kill said 2 meter crocodile. They told me, by using sticks to bash its head in. I asked if I could go along next time they had a “jakaré hape” (or crocodile hunt). They laughed and said “seguaramente”. I was in.

The next evening, while eating our diner of a spectacularly prepared section of crocodile tail, Don Jervacio told me that they would be leaving the following morning at 5:30 am to revisit the lines they had set in the swamp. He asked if I still wanted to come and I think my smile responded for me. The next day, before the sun had even risen, we began the 5 kilometer hike toward the marsh. I was wearing a flannel shirt, jeans and hiking shoes, all of which I would later regret. My companions (Don Jervacio and Don Felix, another neighbor) wore thin pants, fleece sweatshirts and ‘water shoes’ which they had sewn together from old car tires. They looked slightly elvish to me, but the creativity and practicality of these shoes could not be questioned as I would soon find out the hard way.

We descended from the heights of Guido Almada through some pasture land giving an excellent view of the massive size of wetlands before us. From this vista, it all just seemed like an endless sea of grass, but what these tall plants concealed I would soon discover. We passed through some woods before reaching its abrupt edge. Don Felix searched the brush briefly and presented me with his quarry: a stick roughly as wide as golf club and as long as a baseball bat.

This, he told me quite seriously, was a very important tool that I was to keep with me the entire time we were in the estero. It would be used for balance, for bridging small streams and deep pools of water, and ultimately, as a bludgeon for smashing the head of a thrashing crocodile. I have to admit, I was hoping for something more imposing, something with more girth, perhaps something more along the lines of a ‘log’ then just a ‘stick’, however, I had little time to voice my protest. We were soon out of the forest and had entered the marsh. Before me now, the grass grew twice as high as my head. A narrow channel had been burrowed through it by fishermen and crocodile hunters, a path leading twisty-turvy towards a river buried in the midst of this forest of unworldly grasses and reeds.

My two neighbors plunged forwards without a moment of hesitation and I followed. The path was muddy but manageable for approximately 10 meters; it then proceeded to become knee to thigh deep mud. As Don Jervacio and Don Felix sprinted ahead like little sprightly wood nymphs, I struggled to keep pace, cursing and finding myself buried to the hip in mud (and I mean this quite literally) within a few minutes. To my surprise, I was not the last one in our little group. From my home (at this point 5 kilometers away), my dog, Lobo, had followed us. He was determined to go the whole way with our group and I was surprised to turn around and see him trotting up the trail with his tail wagging (his 45 pounds of weight falling lightly on the mud).

For about 2 kilometers, we penetrated the thick vegetation of the marsh--this was quite evidently not a place made for people to wander. The place was alive with animals, the grasses seemingly groping and grasping for stray feet and arms as if they were alive. It was like the movie labyrinth (except sadly minus gremlins and David Bowie) and I kept thinking that I may never make it out of this place. We crossed several small streams less than a few feet wide but well over my head’s height in depth. At each crossing, Lobo sat on the opposite bank crying for a few seconds before he mustered up the courage to take the plunge. I should just say this now, Lobo followed us the entire way--everything that we did, he did as well, and for no other reason that he didn’t want to let me go alone. He really is an awesome dog.

Soon we were in the heart of the estero, at the bank of a river about 10 meters across and of unknown depth. We rested for a few minutes and ate breakfast. Lobo, shivering and eating the scraps of mandioca and tortillas, looked up at me with an unforgettable face that seemed to say, “You know I am going to follow you anywhere, but do we have to keep going?”.

At this point, I finally had a moment to look around me and take in my surroundings. We were in the middle of absolute nowhere, the wildest place that I have ever been in my life that was not part of a national park. This is Paraguay: such few people and such huge pieces of unadulterated land that are both unexplored and completely untamed. Before me, a river with huge numbers of fish and crocodiles and amphibians and who-knows-what-else. Around me, the bird life was like a living, breathing kaleidoscope--6 or more species of water foul, untold numbers of marsh-birds, wading-birds, song-birds, everything-else-birds. Snail kites swarmed and cackled overhead, feasting on an endless food supply between the grasses below. Don Jervacio tells me that I am the first American to have ever been in this part of Paraguay, into the middle of this swamp. The only other people that have come this far are the fishermen, who float out into the river on their little rafts that they build from the reeds and rushes, and the local hunters who set lines for their bounty on the edge of the river. Lobo, I am sure, is the first dog to have made it this far. Still, the day is not over, we are about to go even farther.

We set off again, this time in search of a river crossing. As we walk, Don Felix and Don Jervacio check the lines they have set. All are empty. When we reach the crossing (or as my Paraguayan friends called it, the ‘bridge’) I am not as terrified as I should have been. Not to worry, the fear soon set in. I began to wade across a series of tangled plants, which provided moderate buoyancy from their mass of tangled roots. Soon, however, my weight is too much and they begin to sink. My comrades urge me forward saying that this is fine and completely normal, to just go slow and keep moving.

Then it happens. I am up to my chest in water, backpack being held over my head, still not touching the bottom of this river when the question that I should have been asking all along finally arises, “What the hell am I doing?” I realize that these crocodiles (over 2 meter long crocodiles, mind you) are not on any of our lines meaning that they are still in the water. And now I am in the water. And there is not a chance in hell that I am going to get to a hospital before I bleed out if a crocodile gets my leg (assuming I survive its attack that is). I ponder the stick that I have been given and have so far kept with me as a means of defense. My fear is not abated in the slightest. I am, for the first time in a long time, legitimately concerned for my life. I look back to the bank and there is Lobo, tail wagging, still shivering and looking back at me. We have already come this far, why not a little farther. I finish the crossing, we check the rest of our lines and find them all empty. My neighbor laughs and says that I’ll just have to come back with them some other time for a jakaré. I agree. We definitely have had ourselves an adventure and I really, really want to see one of these crocodiles.

By the time we get back home, I am absolutely covered in mud. My clothes will never come completely clean. Lobo is even dirtier, his hair matted and crusted with dried mud, tail still wagging. As I attempt the fruitless task of cleaning myself off I realize several things. First, this is a brilliant and amazing country, still wild and free like the West was for the first pioneers. There are so many natural resources here, it is almost unimaginable. Second, I am no longer a Peace Corps volunteer, I am a neighbor. Don Jervacio, Don Felix and other families are not people I work with but people I live with. They invite me into their homes, help me when I have problems, laugh with me, share their food, their hospitality, their yerba, their tobacco and their smiles. They are my friends. Thirdly, I have unintentionally adopted a dog that will follow me everywhere. Lobo may be the mangiest, surliest, dirtiest animal I have ever met, but he is my best friend out here so far from my friends back at home, and he will stand by me through anything, no matter how insane it may seem. I am home.

From home,

little hupo

Several days ago, while drinking tereré with my neighbor, Don Jervacio, I was invited to diner with him and his family the following evening. I agreed happily and asked what we would be having to which he nonchalantly responded in Guarani, “Ja’uta jakaré” (translating directly to mean: we are going to eat crocodile). I was intrigued for several reasons:

- Crocodile is delicious (for those who have never tried it).

- This is yet another exotic Paraguayan food to add to my increasing repertoire.

- I had no idea how he had managed to get a crocodile. In my calculation the nearest source of water is quite far away, indeed.

I proceeded to ask how far away this river was. They informed me that it was not far, only five kilometers or so. I asked how large was the crocodile they had killed. They informed me that it was a little over 2 meters (that is well over 6 feet, an animal large enough to take down a cow, let alone a person). I asked them how they managed to kill said 2 meter crocodile. They told me, by using sticks to bash its head in. I asked if I could go along next time they had a “jakaré hape” (or crocodile hunt). They laughed and said “seguaramente”. I was in.

The next evening, while eating our diner of a spectacularly prepared section of crocodile tail, Don Jervacio told me that they would be leaving the following morning at 5:30 am to revisit the lines they had set in the swamp. He asked if I still wanted to come and I think my smile responded for me. The next day, before the sun had even risen, we began the 5 kilometer hike toward the marsh. I was wearing a flannel shirt, jeans and hiking shoes, all of which I would later regret. My companions (Don Jervacio and Don Felix, another neighbor) wore thin pants, fleece sweatshirts and ‘water shoes’ which they had sewn together from old car tires. They looked slightly elvish to me, but the creativity and practicality of these shoes could not be questioned as I would soon find out the hard way.

|

| The view of the marsh expanding to the horizon as seen from the hilltops of Guido Almada. |

|

| A picture of my mud covered pants and shoes following the hike. Also, for scale, I have included the all-important stick that I was given preceding the day's madness. |

My two neighbors plunged forwards without a moment of hesitation and I followed. The path was muddy but manageable for approximately 10 meters; it then proceeded to become knee to thigh deep mud. As Don Jervacio and Don Felix sprinted ahead like little sprightly wood nymphs, I struggled to keep pace, cursing and finding myself buried to the hip in mud (and I mean this quite literally) within a few minutes. To my surprise, I was not the last one in our little group. From my home (at this point 5 kilometers away), my dog, Lobo, had followed us. He was determined to go the whole way with our group and I was surprised to turn around and see him trotting up the trail with his tail wagging (his 45 pounds of weight falling lightly on the mud).

|

| A view of the muddy and almost impassable 'trail' through the marsh complete with its towering grasses. Lobo is leading fearlessly leading the way. |

For about 2 kilometers, we penetrated the thick vegetation of the marsh--this was quite evidently not a place made for people to wander. The place was alive with animals, the grasses seemingly groping and grasping for stray feet and arms as if they were alive. It was like the movie labyrinth (except sadly minus gremlins and David Bowie) and I kept thinking that I may never make it out of this place. We crossed several small streams less than a few feet wide but well over my head’s height in depth. At each crossing, Lobo sat on the opposite bank crying for a few seconds before he mustered up the courage to take the plunge. I should just say this now, Lobo followed us the entire way--everything that we did, he did as well, and for no other reason that he didn’t want to let me go alone. He really is an awesome dog.

Soon we were in the heart of the estero, at the bank of a river about 10 meters across and of unknown depth. We rested for a few minutes and ate breakfast. Lobo, shivering and eating the scraps of mandioca and tortillas, looked up at me with an unforgettable face that seemed to say, “You know I am going to follow you anywhere, but do we have to keep going?”.

|

| Lobo giving me the "Seriously dude, do we have to keep going" look. |

At this point, I finally had a moment to look around me and take in my surroundings. We were in the middle of absolute nowhere, the wildest place that I have ever been in my life that was not part of a national park. This is Paraguay: such few people and such huge pieces of unadulterated land that are both unexplored and completely untamed. Before me, a river with huge numbers of fish and crocodiles and amphibians and who-knows-what-else. Around me, the bird life was like a living, breathing kaleidoscope--6 or more species of water foul, untold numbers of marsh-birds, wading-birds, song-birds, everything-else-birds. Snail kites swarmed and cackled overhead, feasting on an endless food supply between the grasses below. Don Jervacio tells me that I am the first American to have ever been in this part of Paraguay, into the middle of this swamp. The only other people that have come this far are the fishermen, who float out into the river on their little rafts that they build from the reeds and rushes, and the local hunters who set lines for their bounty on the edge of the river. Lobo, I am sure, is the first dog to have made it this far. Still, the day is not over, we are about to go even farther.

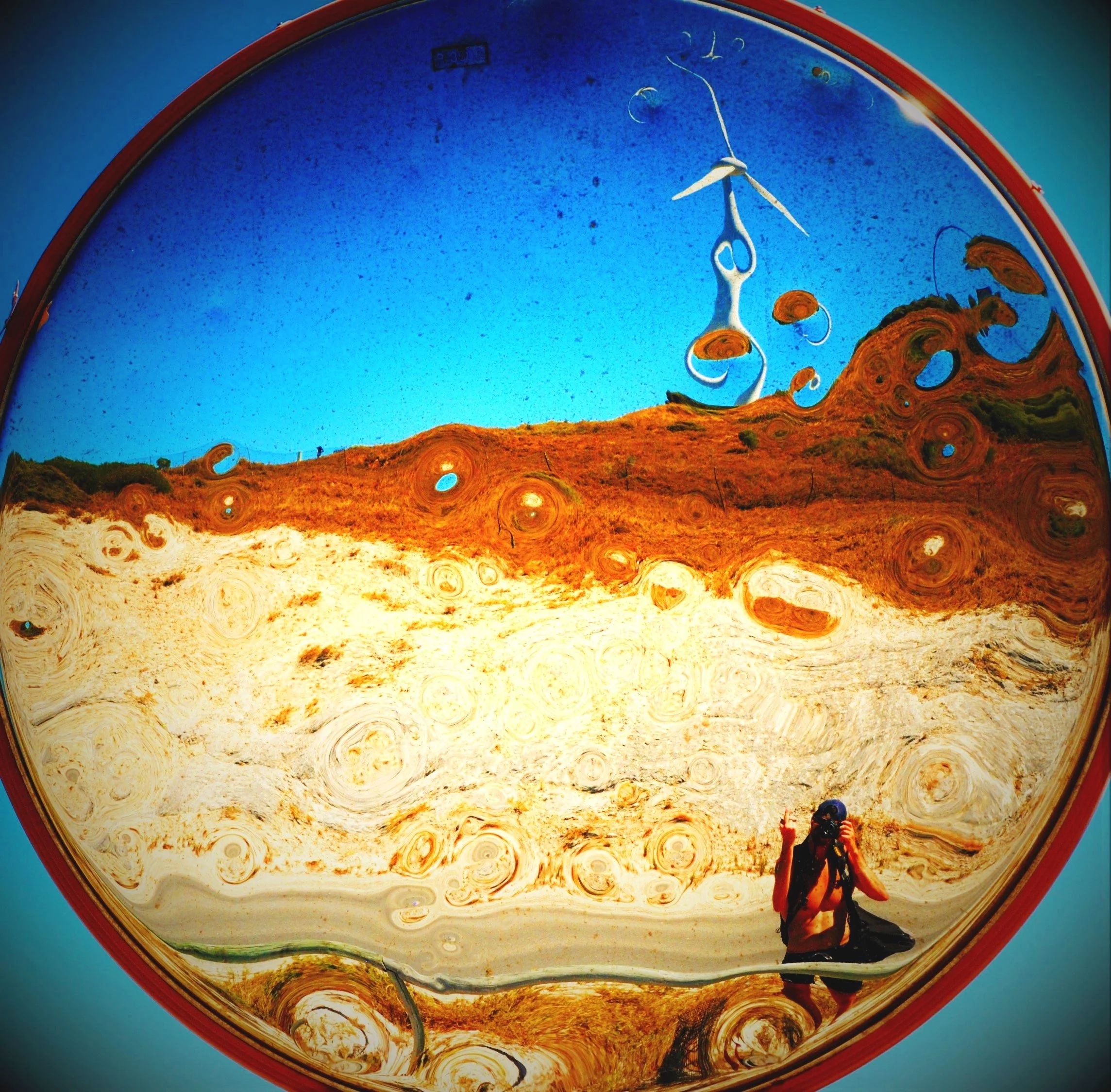

|

| A view from the heart of the estero. The same endless expanse stretches forth in all directions. |

We set off again, this time in search of a river crossing. As we walk, Don Felix and Don Jervacio check the lines they have set. All are empty. When we reach the crossing (or as my Paraguayan friends called it, the ‘bridge’) I am not as terrified as I should have been. Not to worry, the fear soon set in. I began to wade across a series of tangled plants, which provided moderate buoyancy from their mass of tangled roots. Soon, however, my weight is too much and they begin to sink. My comrades urge me forward saying that this is fine and completely normal, to just go slow and keep moving.

Then it happens. I am up to my chest in water, backpack being held over my head, still not touching the bottom of this river when the question that I should have been asking all along finally arises, “What the hell am I doing?” I realize that these crocodiles (over 2 meter long crocodiles, mind you) are not on any of our lines meaning that they are still in the water. And now I am in the water. And there is not a chance in hell that I am going to get to a hospital before I bleed out if a crocodile gets my leg (assuming I survive its attack that is). I ponder the stick that I have been given and have so far kept with me as a means of defense. My fear is not abated in the slightest. I am, for the first time in a long time, legitimately concerned for my life. I look back to the bank and there is Lobo, tail wagging, still shivering and looking back at me. We have already come this far, why not a little farther. I finish the crossing, we check the rest of our lines and find them all empty. My neighbor laughs and says that I’ll just have to come back with them some other time for a jakaré. I agree. We definitely have had ourselves an adventure and I really, really want to see one of these crocodiles.

|

| The gorgeous river buried in the middle of the nearly impassable marsh. The animal life was almost as astonishing as the near pristine state of this ecosystem, especially in the early morning light. |

By the time we get back home, I am absolutely covered in mud. My clothes will never come completely clean. Lobo is even dirtier, his hair matted and crusted with dried mud, tail still wagging. As I attempt the fruitless task of cleaning myself off I realize several things. First, this is a brilliant and amazing country, still wild and free like the West was for the first pioneers. There are so many natural resources here, it is almost unimaginable. Second, I am no longer a Peace Corps volunteer, I am a neighbor. Don Jervacio, Don Felix and other families are not people I work with but people I live with. They invite me into their homes, help me when I have problems, laugh with me, share their food, their hospitality, their yerba, their tobacco and their smiles. They are my friends. Thirdly, I have unintentionally adopted a dog that will follow me everywhere. Lobo may be the mangiest, surliest, dirtiest animal I have ever met, but he is my best friend out here so far from my friends back at home, and he will stand by me through anything, no matter how insane it may seem. I am home.

From home,

little hupo