There is a boy who lived in Guido

Almada. His name was Ivan Fariña

and when I arrived in that place sometime in December of 2011, he was

only 2 years old. At the time, he was just learning to speak and as

he began juggling Guarani and Spanish, like most young Paraguayans

do, he also began incorporating me into his daily life. I worked

extensively with his family over my time in Paraguay and his home

became one of my favorite and most frequented stops on my rounds

through the community or for parties or during the holidays.

Ivan

was a troublemaker. He loved finding his boundaries, testing his

limits and then stepping over the lines ever so slightly. He was an

incredibly smart little kid although he never learned to pronounce my

name properly. To him, I was always “Mano”, the name he would

yell from his grandfather's lap every-time he saw me approaching. He

knew how to endear himself to people, if at the same time also push

their buttons. And he was a total ladies man.

I

cared deeply about this boy. I spent many afternoons watching over

him while his parents were out in the fields and tending to the

animals. I helped him eat and kept him in line during some meals when

his mother was too busy to babysit. We played with his few little toy

trucks in the dirt patch in front of his house. We kicked the soccer

ball. He was a happy, bright, beautiful little boy. After two years

and countless time together, I came to love him very much.

Ivan

was never a sick boy, at least no more so than any other poor

Paraguayan children tend to be. Of the few times I remember him being

ill, it hardly ever seemed to sap his energy and certainly never

diminished his spirit.

The

week after I left Paraguay, Ivan became very sick. He was

hospitalized for several weeks, then a month. It seemed like he was

getting better although so much time certainly took its toll on his

small 4-year-old frame. I imagine his body becoming worn and ragged

by some disease that he just couldn't seem to shake, but his smile,

his light, never dimming even for a minute. Then several nights ago I

got the news: at 10 pm, Ivan passed away. A child, a little 4 year

old boy, a beloved son and a grandson, my little buddy, fell victim

to some illness, some terrible disease, to the poverty of his people.

He was dead. That light had been irrevocably extinguished.

The

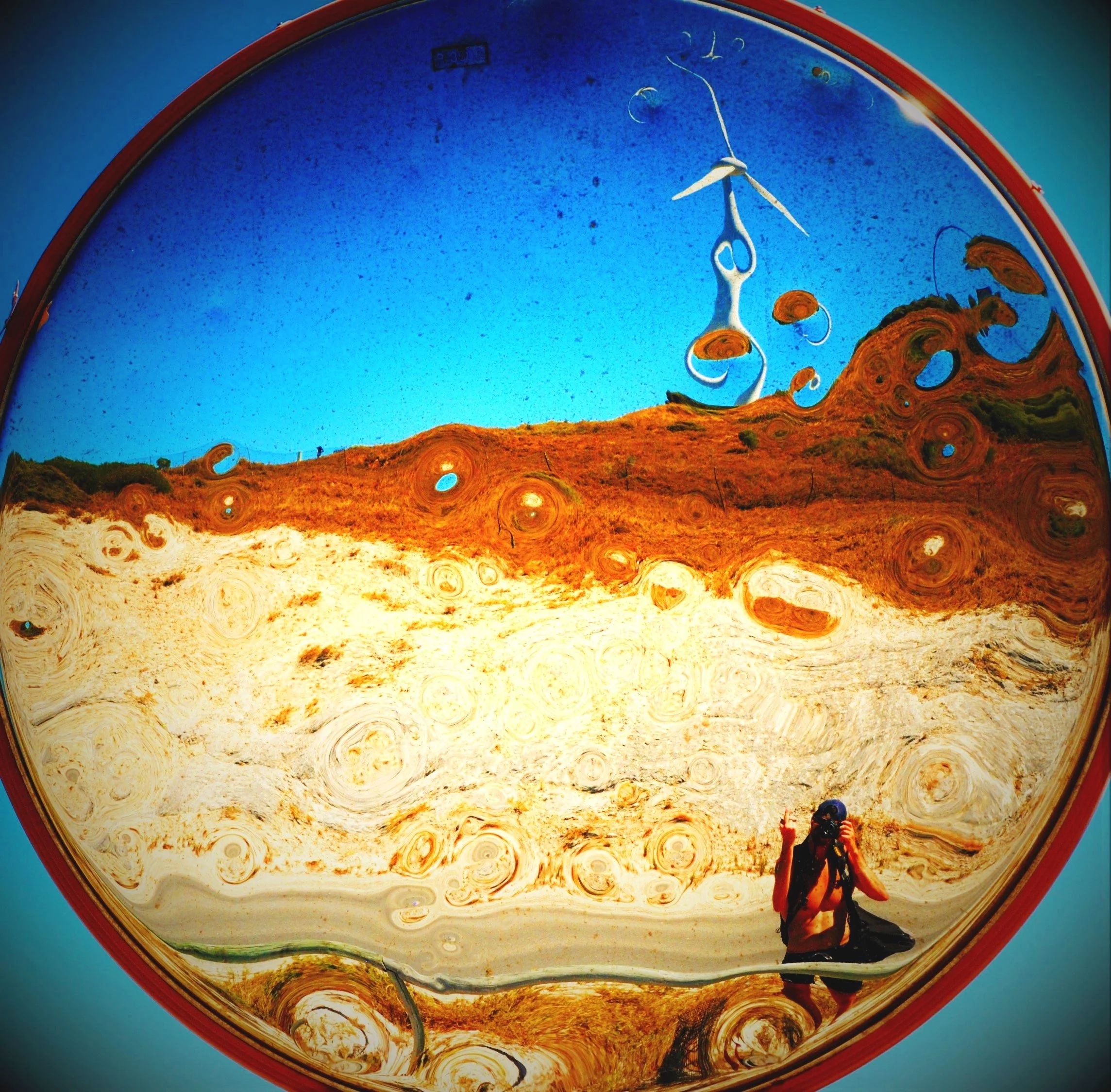

cemetery in Guido Almada is not large. The community itself is

comparatively new and though many people have passed, the plots are

modest, as much a product of economics as necessity. I have been

there many times. I have prayed there many afternoons. It is a

beautiful place, beautifully Paraguayan in its setting and the

surrounding landscape. But it belies one subtle and yet heartbreaking

reality: most of the graves are small. Child sized.

Child

mortality, something heartrendingly inconceivable to many in the

developed world, is something much too common for children and

families in the developing world. Out of all the families I lived and

worked with during my time in Paraguay, all of them had either lost a

son or a daughter, a brother or a sister, or a cousin at some point

in their lives. In the absence of decent medical care and without the

financial means to access the paltry facilities that do exists,

people face death—real, tragic, human death—as a matter of their

daily lives. Women must give birth to stillborn babies. Parents must

watch helplessly as their children wither away. Brothers and sisters

must say goodbye to their closest companions before the age when they

can understand what death is all about.

I

don't mean to paint a picture of some sort of hell or holocaust.

Surely, it is not so bad and for the most part, despite their poverty

and circumstance, these people live happy lives. But we should not

forget: the chasm between the developed and developing world still

exists today and we should do everything in our power, especially in

this modern day in age, to close that distance. I don't care with

what religion or political ideology you affiliate; I don't care how

you label yourself or what you feel your moral obligation is to the

world: the fact that daily thousands of children die of preventable

diseases, malnutrition, and neglect is simply unacceptable. In our

own way, we all bare some of the blame and some of the responsibility

for this state of our world. Even you. Even me.

I

wrote the preceding few paragraphs some weeks ago. I didn't have the

words (and still don't) for so much of what this transition home from

the Peace Corps has been like. I have almost decided to give up on

trying to communicate it entirely. If anything, that is what two

years in the campo have done for me: made me really good at dealing

with my own shit without relying on others. Still, I have forced

myself to write this story down and share it with people—for Ivan's

sake and for the sake of the thousands of other starving, sick, dying

children there are in the world tonight.

When

I received the news of Ivan's passing, I felt as if my heart fell

straight down and out of my body. My lungs stopped working. I broke

down into a pile of sobbing, chaotic tears. I didn't know what to do,

how to help, and I couldn't begin to imagine the emptiness that my

friends, my community, my Peace Corps family must be feeling. For

them, I have few words except for I love you, I will always remember,

and I am sorry I had to leave when I did. I wish I could be there to

share the heartbreak with you. I hope you know how much I care.

So

as I exorcise these last emotional demons from a body and mind that

has been so thoroughly (and thankfully) ravaged by two years of life

in a poor Paraguayan community, I hope that I can move on with a

purpose. That I can take the lessons I have learned, the lives I have

shared, and the love I have been given and make a difference in this

world. And even though I daily feel as if I am now living and working

in his memory, it is too late for Ivan, but not for the countless

thousands of others out there.

I

love you, little buddy. I miss you. I will remember you always.

-little

hupo