The Don who lost his wife just 2 months earlier stood before me in his tan slacks and open-chested, blue shirt. His disheveled cowboy hat, resembling something one might find at a rest stop on the US interstate, was cocked back on his brow. He squinted in the sunlight as he explained that here in this quiet, wind-swept cemetery lay his wife, her name carved into a small cross at the head of her tomb. He hadn’t shaven in a few days and I thought could sense a sadness in his words although, if this was true, he did little else to betray his feelings. Paraguayan men don’t really cry, or at least thats what they say. Maybe it’s the machismo or maybe its just the same sense of masculinity that has gendered emotions across the globe. Maybe, however, it has more to do with the nature of death as it manifests itself in this place and among Paraguayan people. You see, Paraguayans don’t bury their dead. In this culture, dying is a process that continues long after one’s heart stops beating.

If one visits a Paraguayan cemetery, several features seem to stand out immediately. The rows of tombs are wider and longer, more like streets than aisles. And, seemingly as a way to solidify this fact, Paraguayans will often label these rows with street names written on street signs (at least in the larger cemeteries). The tombs (called pantheones by Paraguayans), are much more than just carved headstones laid in the ground. Each pantheon resembles an above ground alter. For the poorer families, this is often little more than a block of concrete or a small brick structure adorned with a small casita (or ‘little house’ in English) at its head. The deceased is placed inside on the day he/she is laid to rest. In the following months, usually on the one-month, two-month, or three-month anniversary of his/her death, the family will revisit the pantheon to decorate with colored tiles, flowers (in the case of this Don, small flowers placed in make-shift pots made from recycled soda bottles), trinkets or other small items.

For the wealthier families, or at least those with more to invest (financially or emotionally) in such an endeavor, the pantheon can assume a much more prominent state. Socio-economics, it seems, plays out even in the afterlife. Sometimes, the pantheon itself can resemble more of a mausoleum that rival both in size and structural integrity the very houses in which many Paraguayans live. While most rural homes are made of mud-brick or wood-slats, the cemeteries are often mistakable for communities themselves with towering, concrete rooms dedicated to a dead family member or several. The priorities between the living and the dead are skewed in a way that differs largely from other cultures I have experience and particularly from US culture. This may be tied up somehow with the religious tendencies of these people (this country is predominantly Catholic). It may also have something to do with the connections of many Paraguayan people to indigenous practices or histories. This is entirely speculation on my part, but this also seems to be a reoccurring theme among the ideological clashes between Europeans and native peoples both during and after the conquest of South America.

Regardless, it is amazing the reverence that people in this culture hold for death--the allocation of resources (especially in a country with a large portion of the population living in poverty), the regard in which people dedicate time and energy toward post-death rituals (for months and years, even decades following), and the way that all of this falls in stride with the daily lives of most Paraguayans. When one dies, the anniversary of their death and birth are observed during week-long events for the first few years following their passing. Then, for the next several decades, smaller but still significant observances are continually held to commemorate these important dates. The dead do not die, at least not until their living memory is lost with the passing of the next few generations.

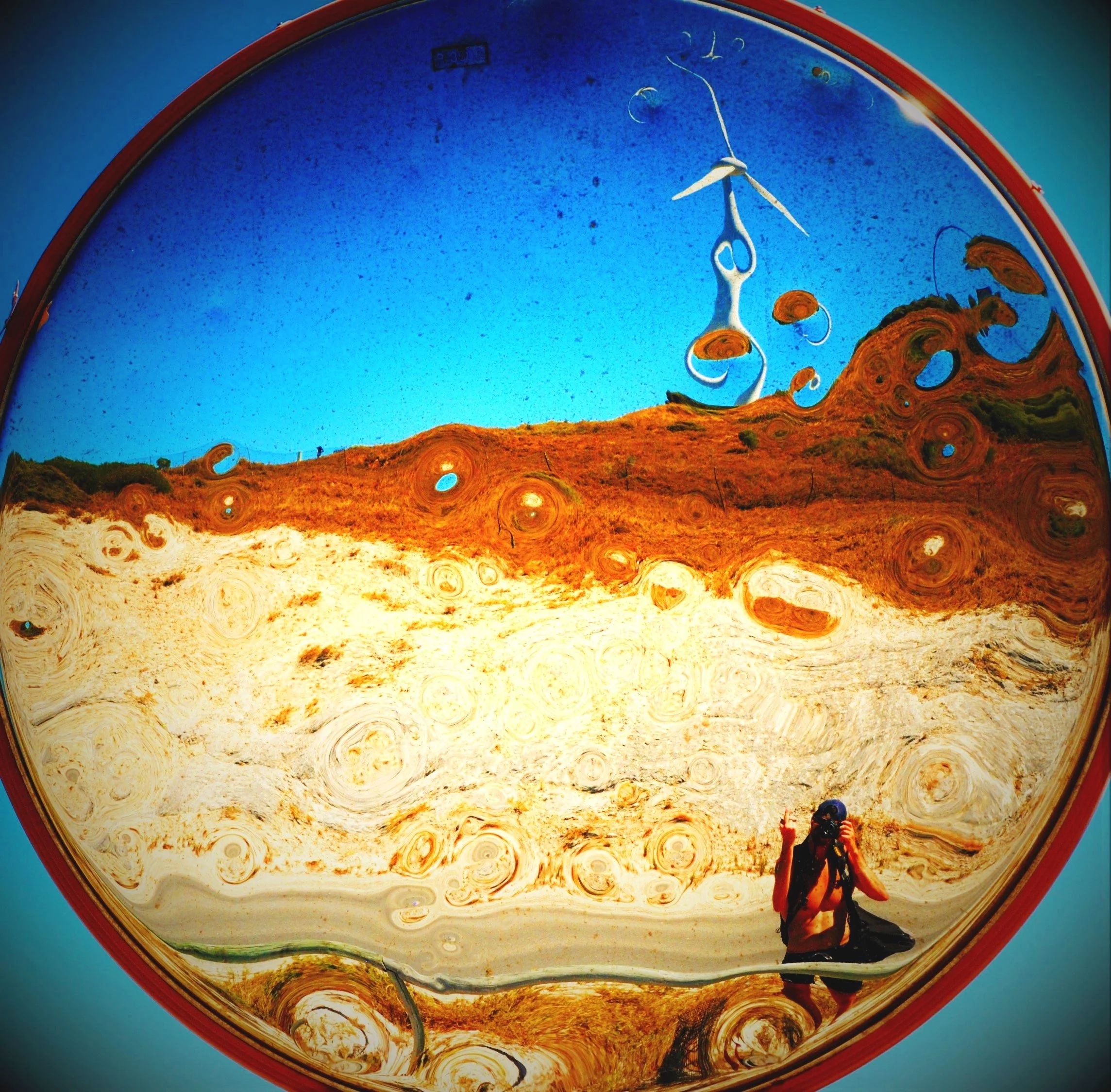

The north wind is blowing hard through the palms when we finish working. It is late morning and the sun is now playing kaleidoscope between the branches and through the grasses of this tropical landscape. It is going to rain tomorrow, the Don tells me. His wife’s tomb looks only slightly better than it did an hour before--the weeds have been cleared, a fresh layer of concrete added to the exterior. He wants to add tiles to the outside; he thinks that blue would look nice. We leave the cemetery and the mood is not solemn, not melancholy or even sad in the slightest. There is more work to be done. The fields must be hoed, the crops harvested, the beans dried and the garden tended. And so our day continues, only an hour later than it would have otherwise, and with my head pondering the matter-of-fact nature in which we visited death for the morning.

from the cemetery,

-little hupo

If one visits a Paraguayan cemetery, several features seem to stand out immediately. The rows of tombs are wider and longer, more like streets than aisles. And, seemingly as a way to solidify this fact, Paraguayans will often label these rows with street names written on street signs (at least in the larger cemeteries). The tombs (called pantheones by Paraguayans), are much more than just carved headstones laid in the ground. Each pantheon resembles an above ground alter. For the poorer families, this is often little more than a block of concrete or a small brick structure adorned with a small casita (or ‘little house’ in English) at its head. The deceased is placed inside on the day he/she is laid to rest. In the following months, usually on the one-month, two-month, or three-month anniversary of his/her death, the family will revisit the pantheon to decorate with colored tiles, flowers (in the case of this Don, small flowers placed in make-shift pots made from recycled soda bottles), trinkets or other small items.

For the wealthier families, or at least those with more to invest (financially or emotionally) in such an endeavor, the pantheon can assume a much more prominent state. Socio-economics, it seems, plays out even in the afterlife. Sometimes, the pantheon itself can resemble more of a mausoleum that rival both in size and structural integrity the very houses in which many Paraguayans live. While most rural homes are made of mud-brick or wood-slats, the cemeteries are often mistakable for communities themselves with towering, concrete rooms dedicated to a dead family member or several. The priorities between the living and the dead are skewed in a way that differs largely from other cultures I have experience and particularly from US culture. This may be tied up somehow with the religious tendencies of these people (this country is predominantly Catholic). It may also have something to do with the connections of many Paraguayan people to indigenous practices or histories. This is entirely speculation on my part, but this also seems to be a reoccurring theme among the ideological clashes between Europeans and native peoples both during and after the conquest of South America.

Regardless, it is amazing the reverence that people in this culture hold for death--the allocation of resources (especially in a country with a large portion of the population living in poverty), the regard in which people dedicate time and energy toward post-death rituals (for months and years, even decades following), and the way that all of this falls in stride with the daily lives of most Paraguayans. When one dies, the anniversary of their death and birth are observed during week-long events for the first few years following their passing. Then, for the next several decades, smaller but still significant observances are continually held to commemorate these important dates. The dead do not die, at least not until their living memory is lost with the passing of the next few generations.

The north wind is blowing hard through the palms when we finish working. It is late morning and the sun is now playing kaleidoscope between the branches and through the grasses of this tropical landscape. It is going to rain tomorrow, the Don tells me. His wife’s tomb looks only slightly better than it did an hour before--the weeds have been cleared, a fresh layer of concrete added to the exterior. He wants to add tiles to the outside; he thinks that blue would look nice. We leave the cemetery and the mood is not solemn, not melancholy or even sad in the slightest. There is more work to be done. The fields must be hoed, the crops harvested, the beans dried and the garden tended. And so our day continues, only an hour later than it would have otherwise, and with my head pondering the matter-of-fact nature in which we visited death for the morning.

from the cemetery,

-little hupo